How many pounds per square inch of pressure does a lead pipe swung in a downward arc exert upon a human body? What about a night stick or a sap? A baseball bat? A wooden Coca Cola crate? A fist ramped up to speed by hatred, adrenaline and muscle? How about a work boot swung like a pendulum point on to a chest? A dog bite by a 90 pound German Shepard to the stomach or thigh or buttocks? A Monitor Gun? All of these were wielded here, in our country, against men and women, teenagers and children — as were dynamite, shotguns, high powered rifles and pistols, fire and brimstone.

How many pounds per square inch of pressure does a lead pipe swung in a downward arc exert upon a human body? What about a night stick or a sap? A baseball bat? A wooden Coca Cola crate? A fist ramped up to speed by hatred, adrenaline and muscle? How about a work boot swung like a pendulum point on to a chest? A dog bite by a 90 pound German Shepard to the stomach or thigh or buttocks? A Monitor Gun? All of these were wielded here, in our country, against men and women, teenagers and children — as were dynamite, shotguns, high powered rifles and pistols, fire and brimstone.

Nonviolence, a persistent belief in the moral goodness of their cause and an Old Testament faith arrayed themselves against night riders who burned churches and murdered, against Molotov cocktails, against Klansman, against pistol whipping registrars, against shotguns and high powered rifles. And yet, and yet, Bob Moses continued to work in the heart of dangerous country, in Leflore County, Greenwood, Mississippi to register poor sharecroppers to vote. John Lewis offered his body up in Freedom Rides, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth took on Bull Connor again and again in Birmingham, and Septima Clark, one of the great teachers of civil rights workers, continued to train those needed for the renewed conflict.

Nonviolence hung on the edge of obsolescence as bombing succeeded bombing, as Black Churches were burned, as murders and beatings continued with impunity. Sometimes crowds pouring out from bars and pool halls and standing at the boundary of peaceful demonstrations would throw rocks and bottles and bricks when the firehouses were turned on and the dogs charged. More than once King and others had to make personal pleas with frightened, enraged supporters to take their guns home.

How can a body become a weapon without being used in attack? Martin Luther King believed in nonviolence as a method to break the injustice of segregation and oppression. He studied its effectiveness against the British as employed by Gandhi. Many demonstrators were trained in its use. As exercised in the South in this era, it is inextricably tied to the idea of sacrificial love. It becomes a kind of chant, perhaps a psalm — offer your body to the oppressor again and again to “shame them into decency (393).”* Offer your body to be jailed. Offer your body to ensure your right as a citizen to ride a bus, to sit where you wish on that bus, to eat at any lunch counter, to use any bathroom, to receive a good education, to vote. Offer your body to move the conscience of the American public. Offer your body because we are taught as Christians to love our enemies. Nonviolence in the South had its origin point in the Black Church and in the faith that held that most human beings were inherently redeemable. Show segregationists that black people were human beings with the same inherent rights to fair treatment, and you might break their hatred. Even after the worst incident, the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the murder of four little girls, King, sounding almost like Lot arguing with Yahweh, says to President Kennedy, “There are many white people of good will in Birmingham (894).”*

How can a body become a weapon without being used in attack? Martin Luther King believed in nonviolence as a method to break the injustice of segregation and oppression. He studied its effectiveness against the British as employed by Gandhi. Many demonstrators were trained in its use. As exercised in the South in this era, it is inextricably tied to the idea of sacrificial love. It becomes a kind of chant, perhaps a psalm — offer your body to the oppressor again and again to “shame them into decency (393).”* Offer your body to be jailed. Offer your body to ensure your right as a citizen to ride a bus, to sit where you wish on that bus, to eat at any lunch counter, to use any bathroom, to receive a good education, to vote. Offer your body to move the conscience of the American public. Offer your body because we are taught as Christians to love our enemies. Nonviolence in the South had its origin point in the Black Church and in the faith that held that most human beings were inherently redeemable. Show segregationists that black people were human beings with the same inherent rights to fair treatment, and you might break their hatred. Even after the worst incident, the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the murder of four little girls, King, sounding almost like Lot arguing with Yahweh, says to President Kennedy, “There are many white people of good will in Birmingham (894).”*

As he came to national and international attention after the Montgomery bus boycott, he found himself cornered again and again by circumstance and enemies. He was strapped for funds, caught between the great unshackling by thousands of black men and women in dozens of places in the Southern states and the unified resistance of segregationists. He often stumbled. He was jailed, sued, prosecuted, whipsawed by the politics of black pastors and their organizations, pressured to go slow by attorney general Robert Kennedy and the President, stalked by J. Edgar Hoover, a racist and a patient, calculating toad of vast bureaucratic experience and poisonous wiles who gathered evidence of King’s character flaws by virtue of wiretaps permitted by Robert Kennedy. King gave Hoover ammunition. King was no saint. He was a serial adulterer and a man given to “… a powerful appetite for prestige and luxuries… (407).”*

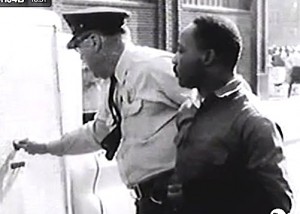

But he was also a man who chose his path: “He believed in and preached in a merited suffering [that] is redemptive, but this is the first time where he consciously chose a path to suffer. I’m going to walk into the teeth of suffering because that’s the only thing I can see here that will… that can rescue this, this huge gamble that we’ve taken. So, he’s, he’s taking a step toward it. Cause’ believe me, he didn’t want to go into the Birmingham jail. And if you see the photographs of the way they’re taking him into the Birmingham jail, he’s a relatively small man and the cops are lifting him up by his pants. There’s no respect for the fact that this is Dr. King. This is somebody that’s going to have a national holiday named for him. This is another nigger going to jail.”#

But he was also a man who chose his path: “He believed in and preached in a merited suffering [that] is redemptive, but this is the first time where he consciously chose a path to suffer. I’m going to walk into the teeth of suffering because that’s the only thing I can see here that will… that can rescue this, this huge gamble that we’ve taken. So, he’s, he’s taking a step toward it. Cause’ believe me, he didn’t want to go into the Birmingham jail. And if you see the photographs of the way they’re taking him into the Birmingham jail, he’s a relatively small man and the cops are lifting him up by his pants. There’s no respect for the fact that this is Dr. King. This is somebody that’s going to have a national holiday named for him. This is another nigger going to jail.”#

Why did he keep going on? At one point in a heated conversation with Robert Kennedy he erupted: “Always King protested, somebody would find a way to make protest unreasonable and segregation reasonable for the moment. ‘We’re tired, very tired,’ he said. ‘I’m tired. We’re sick of it.’ (610).”*

King’s primary weapons were his Christian faith, his voice and his body, and his willingness to believe in an idea ## he paraphrased as such: “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” Encapsulated within the metaphor is a vision of moral progress that depends upon a just and merciful God taking stock of and guiding our best aspirations, but the reference to an uncertain length of time gives no guarantee that he will be present to see justice come. King pitched himself into battle after battle and came to suspect that sometime the bullet meant for him would arrive.

On November 22, King watched the reports come in from Dallas. When the President’s death was announced, King said to Coretta,” I don’t think I’m going to live to reach forty. …. This is what is going to happen to me also. … I don’t think I can survive either (263).”**

Whenever he might have taken a long pause from the civil rights’ movement or publically decried the lack of progress and used that as his break-point for a leavetaking, he chose instead to double-down on his commitment. I think he did so because he allied his life with events outside his ability to choose — once he become the iconic spokesman for the movement, how could he leave? He had become his public persona. His ego had to have played a part — he was Martin, the prophet, the last speaker at the 1963 March on Washington, the one black man who carried the most weight with the President of the United States. All the evidence also indicates that he believed in the possibility of reversing the terrible grip of Jim Crow and of 100 years of injustice. Nothing I have read gives any hint that he had become cynical and that his public oratory and his preaching were merely dramatic shows for the masses. For all his failings, he believed in his own words when he said, ” … we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestant and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’ (883).”* He sincerely believed in the whirlwind he had helped unloose.

*Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-1963 by Taylor Branch

#Taylor Branch, interview: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/mlk/filmmore/pt.html

##Theodore Parker was the originator of the metaphor.

**Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King, JR. by Stephen B. Oates