Do you have a conscience? Are you able to look back at your dark acts, see them anew and atone for them? At 17, 18 or 19 years of age, do you cherish your life? No strutting, ‘I’m so  wonderful’ narcissism now — I mean, do you understand the delicacy of its construction, its reliance upon circumstance and chance for its breathing and breathless continuance? Do you recognize its value, the sweet nature of many of its days? Answer yes to these questions and you will better understand King Lear and Shakespeare’s vision of tragedy.

wonderful’ narcissism now — I mean, do you understand the delicacy of its construction, its reliance upon circumstance and chance for its breathing and breathless continuance? Do you recognize its value, the sweet nature of many of its days? Answer yes to these questions and you will better understand King Lear and Shakespeare’s vision of tragedy.

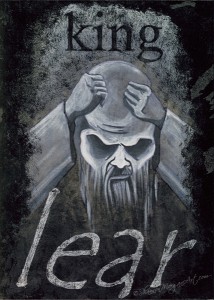

painting by Gil Bruvel for a staging of King Lear

Tragedy and Comedy are separated by the flimsiest of circumstances; we laugh later at close calls where we fumbled and said something ridiculous, but we escaped unscathed. Here is a simple way to tell the difference: Caught with our pants down, we flee the toothy, big bear before he eats us. Getting away is comic. Getting caught is tragic.

Shakespeare’s idea of tragedy has comedic elements; pay attention to the Fool and you’ll see many. His tragic heroes and heroines have goodness in them. They choose their paths. When they fall, we mourn their fall. No one mourns for a villain; for him, our desire for justice supersedes our capacity for mourning.

Shakespeare’s tragic men and women are divided souls. Lear is capable of awful rants, poisonous curses, foolish, stupid actions, but he has a conscience. His suffering is not pointless for it activates his sense of remorse. He seeks forgiveness and earthly redemption.

Shakespeare’s tragedies proclaim that life is the most sacred of possessions. Their darknesses illuminate the affirming force of life itself. That is one reason why his good characters struggle against evil; the preservation of life and goodness is worth the risk of losing life.

Nihilism and tragedy have nothing in common. One asserts that nothing is of value and that cynicism is a quality of high merit; the other asserts that life and tempered virtue are worth all their troubles.

King Lear; painting by Arif Bahtiar

King Lear; painting by Arif Bahtiar

In Post 130 I took you through all of the scenes of Act I. I wanted to orient you to the characters, actions and themes of the play. For Acts II and III I will focus on two speeches, two soliloquies only. You have enough information and background that on your own or in concert with your teacher, you should be able to follow the action and make sense of who is doing what to whom. Right now, I want to take you deeper into two characters.

James Shapiro makes the point that if Shakespeare had cut soliloquies from Hamlet, the action of the play would have run smoothly, uninterrupted. The soliloquies, “if anything, compete with and retard the action (297).”* The same might be argued for King Lear. What his soliloquies do accomplish is to show the interior life of the character — their moral wrestling’s, their wrenching decision making, their secret feelings shown only to us. The soliloquies make his characters human beings and not types. We have to take their complexities into consideration when we judge them; we have to acknowledge that we too have such interior voices at work in us, and that we too struggle to see clearly and act wisely.

In Act II, iii, Edgar speaks directly to us; he has been betrayed by Edmund. He flees for his life into a desolate setting, a place that his father, Gloucester, will describe as empty of shelter. Also deceived by Edmund, his father believes that Edgar has betrayed him. Gloucester sends men to find him. He will be killed if found.

John Hamiliton Mortimer’s Edgar

I heard myself proclaim’d;

And by the happy hollow of a tree

Escaped the hunt. No port is free; no place,

That guard, and most unusual vigilance,

Does not attend my taking. Whiles I may ‘scape,

I will preserve myself: and am bethought

To take the basest and most poorest shape

That ever penury, in contempt of man,

Brought near to beast: my face I’ll grime with filth;

Blanket my loins: elf all my hair in knots;

And with presented nakedness out-face

The winds and persecutions of the sky.

The country gives me proof and precedent

Of Bedlam beggars, who, with roaring voices,

Strike in their numb’d and mortified bare arms

Pins, wooden pricks, nails, sprigs of rosemary;

And with this horrible object, from low farms,

Poor pelting villages, sheep-cotes, and mills,

Sometime with lunatic bans, sometime with prayers,

Enforce their charity. Poor Turlygod! poor Tom!

That’s something yet: Edgar I nothing am.

He cannot escape the country. He has no allies. To survive, he must lose himself in a disguise. He understands enough about the homeless inhabitants of the roads and about human  nature to hide himself within the most despised resident and therefore the most invisible resident. We do not see the person of those for whom we have contempt; we see the type, the sign they represent. He will become a “Bedlam beggar“, a “lunatic” and thus dissolve from sight in plain sight. This entitled young man, the son of a duke, now hunted like a beast, must becaome a human being closest to a beast just to stay alive.

nature to hide himself within the most despised resident and therefore the most invisible resident. We do not see the person of those for whom we have contempt; we see the type, the sign they represent. He will become a “Bedlam beggar“, a “lunatic” and thus dissolve from sight in plain sight. This entitled young man, the son of a duke, now hunted like a beast, must becaome a human being closest to a beast just to stay alive.

His transformation takes up all of one scene; he emerges from darkness into the stage lights just for a flash. Desperate, already having hidden in a hollow tree, he transforms himself in front of us, stripping, caking himself with filth, bloodying his body. Naked, his animal self apparent, he uses a panicky ingenuity to become an ‘other’, a member of the poorest, lowest caste of humanity. In the second to last line of the soliloquy he even practices a new voice. His fine clothes gone, his cleanliness given over to “grime”, his hair wild and elf-knotted, his body pierced, he works to erase everything of Edgar, even the timbre and pitch of sounds that are his only. Everything once Edgar must be submerged into “nothing”. Remember though, this is a man playing at madness. His mind remains untouched. He adopts stealth as his weapon so that one day he might be resurrected and return as another kind of Edgar, one tempered by pain.

Lear is all but broken; he is on the edge of madness, of losing his identity completely. His knights have fled. He staggers through a terrible storm accompanied by the Fool and Kent, still in disguise. They have not fled because their love for him is based on a Lear we have not seen, a man and King capable of producing an abiding loyalty in two men as good as these. For roughly 173 lines, Lear has raged at the storm, at the treachery of Regan and Goneril, at the mysterious presence in life of “filial ingratitude”. Finally, three lines before this soliloquy he makes one more effort to reject self pity and to keep his mind intact, but the back and forth of the lines themselves show his shifting, precarious state:

No, I will weep no more. In such a night to shut me out! Pour on; I will endure. In such a night as this! O Regan, Goneril! Your old kind father, whose frank heart gave all, — O, that way madness lies; let me shun that; No more of that. (III, iii, 17-22) Then he pauses, and one of the electric moments in the play occurs:

woodcut by Claire Van Vliet

Prithee, go in thyself: seek thine own ease:

This tempest will not give me leave to ponder

On things would hurt me more. But I’ll go in.

To the Fool

In, boy; go first. You houseless poverty,–

Nay, get thee in. I’ll pray, and then I’ll sleep.

Fool goes in

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,

And show the heavens more just.

For only the second time in the play (the other occurs in III, ii, 70-73) Lear’s tenderness emerges in an unguarded moment. The Fool should go into shelter before the King. Lear sees  the Fool with a clear, lucid eye as shown in his offhand image — his soaked, cold, penniless Fool as the emblem of “houseless poverty”. That insight as shown in those two words lead Lear toward a universal view of the poor and their tribulations. Now he sees “naked wretches wheresoe’r you are,” in other words, all who suffer whether he knows them or not. He imagines them out in “this pitiless storm”, that same storm that also persecutes “a head so old and white as [his] (III, ii, 23-23).”

the Fool with a clear, lucid eye as shown in his offhand image — his soaked, cold, penniless Fool as the emblem of “houseless poverty”. That insight as shown in those two words lead Lear toward a universal view of the poor and their tribulations. Now he sees “naked wretches wheresoe’r you are,” in other words, all who suffer whether he knows them or not. He imagines them out in “this pitiless storm”, that same storm that also persecutes “a head so old and white as [his] (III, ii, 23-23).”

charcoal by Shannon Morgan

He returns to the word “houseless” and in lines of wonderful compression sees for the first time other elements of their misery — their hunger or “unfed sides,” an image that suggests the sight of the bones in the bodies of the starving; their “loop’d and window’d raggedness” continues the idea of a house in human form in an impression of shredded rags of clothing as only an exposed and useless shield against the weather.

The “seasons against which they must protect themselves” expands their catalog of hardships to active persecutions by the powerful. That thought immediately leads Lear to his own failings as King. His arrogance spent, humility takes its place. He speaks as one who was “pomp” and says that the powerful should “physic” themselves, purge themselves of their pride and belief in their superiority and “feel what wretches feel.” They should make the leap to an empathetic vision that provokes them to do what they can to “show the heavens more just.” This humbled, ragged man, no longer a king, adrift and hunted, had to suffer complete deprivation so that he could find a beginning of a redemptive possibility. And then Edgar shatters this peace, and Lear loses the last underpinnings to his sanity, but his madness possesses its own terrible lucidity.

From there Act III builds in intensity. A strange, profound trial occurs, and in scene vii, we witness perhaps the most brutal passage in his great plays.

a moment from scene vii as performed by the Goodman Theater in Chicago in 2006-2007

a moment from scene vii as performed by the Goodman Theater in Chicago in 2006-2007

* 1599: A Year in the Life of Shakespeare by James Shapiro