I have a passing understanding of why some high school kids pitch their heads back into self-induced seizure-comas when their teacher announces that this term they will read X, Y or Z by “the greatest writer of the English Language.” They instantly imagine droning days of feeble readers delivering some crap about fussy men and women who cannot decide or who decide badly and all this in language that sounds as if Sir Percy SnootyPantaloons were speaking about the social lives of the most monotonous old people ever imagined. Oh, and in your fever you can see class time stretching out and away until you are old and useless and still sitting in these same spine-melting desks and all of those unrelieved convulsion-inducing lectures and recitations will go on and on until you pray for your high school to be invaded by xenomorphs.

I have a passing understanding of why some high school kids pitch their heads back into self-induced seizure-comas when their teacher announces that this term they will read X, Y or Z by “the greatest writer of the English Language.” They instantly imagine droning days of feeble readers delivering some crap about fussy men and women who cannot decide or who decide badly and all this in language that sounds as if Sir Percy SnootyPantaloons were speaking about the social lives of the most monotonous old people ever imagined. Oh, and in your fever you can see class time stretching out and away until you are old and useless and still sitting in these same spine-melting desks and all of those unrelieved convulsion-inducing lectures and recitations will go on and on until you pray for your high school to be invaded by xenomorphs.

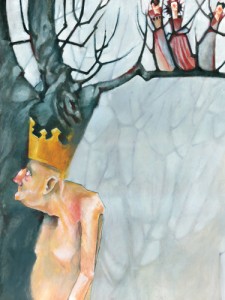

I am no scholar, but I love King Lear. I am going to try to write about all five Acts of King Lear in such a way that you can make sense of it. I intend You to be a high school senior or a freshman in college. That is who I will have in mind when I am rereading the play and writing about it.

You have opened the play to Act I, Scene 1. Forget Kings. Forget medieval robes. Forget history. Think about these characters as resembling the human beings who walk around in your world, ones you know who are foolish or loyal, old and arrogant, insightful and treacherous, afraid, loving, desperate and even brave. Think about those who have a strain of nobility in them, who might be capable of heroic acts. Think about those who have a nasty edge to them and who might be capable of much worse if you ever got in their way or they ever wanted something from you. If you can do this, you can imagine the characters of King Lear.

Next, take the language slowly. Make it as conversational as you can. Follow the verbs. They will point you toward the action, and in Shakespeare, action is often mixed with profound meanings. Pay attention to footnotes. They can lead you out of difficult passages. Use Spark Notes only when you lose your way in an especially dense thicket. Read King Lear, but make sure you know what is going on.

In the Chorus of Henry the Fifth Shakespeare reminds us that the imaginative “burden … falls squarely on the playgoers: ‘Think , when we talk of horses, that you see them.’ The play will fail without [your] imaginative effort (87).” * You have to reach beyond your normal academic self to understand this play. If you fail, the play is not at fault. You have failed to measure up to its demands.

The characters and setting: The Lear family: Lear, King of Britain and his three daughters, Goneril (wife of Albany) , Regan (wife of Cornwall) and Cordelia (to be the wife of the King of France); his retainers, Kent and the Fool. The Gloucester family: Gloucester and his sons, legitimate Edgar and bastard Edmund.

As he also does in Othello, Shakespeare begins King Lear in the middle of a conversation between two men; something is wrong. Within 4 lines we know that there is a potential rivalry for power, and that the King, often a figure of stability and harmony, is dividing his kingdom. WHAT!!?? A King is the State. Death is expected but not retirement. Who will rule? Competition for power invites instability, plots, families torn asunder.

Then the conversation abruptly shifts and within 25 lines we listen as a father (Gloucester) calls his illegitimate son’s mother a whore, boasts of his time in bed with her, and asks his companion whether he observes any fault in this son because of his status as a bastard. Gloucester does all this in the presence of Edmund, the son. Place yourself in Edmund’s position. Wouldn’t you be furious?

In the first 25 lines of the play Shakespeare lays out the public, political and personal fault lines that will govern the play and provide its forward movement. The nation will fracture. Families will implode. Individuals will be swept away in the maelstrom.

In the first 25 lines of the play Shakespeare lays out the public, political and personal fault lines that will govern the play and provide its forward movement. The nation will fracture. Families will implode. Individuals will be swept away in the maelstrom.

King Lear enters and with the impatience of autocratic, old men he utters immediate commands; no small talk for him, no kind words, no jokes. He has a kingdom to divide among his three daughters, the map already completed, so that he may “unburthen’d crawl toward death (I, i, 42).”

The problem — he should not abdicate power because he is tired. His responsibilities are to his people first, not to his body. He will now set in motion forces which will unleash banishment, torture, murder and civil war.

banishment, torture, murder and civil war.

Illustration by Ana Benaroya

Of course, in his arrogance Lear believes that his actions will ensure “that future strife may be prevented now (I, i, 45).” He acts as if he is omniscient, as if his power as king gives him power over a future when he will no longer be king. His blindness and complacent faith in a future he believes is set precede his fall.

Then, in what appears to be a capricious act, a whim, he asks his daughters to compete for “our largest bounty” by publicly describing their love for him. He makes familial love a game to be fought over ruthlessly. He connects the intimacy of family to the corruption implicit in scrambling for power.

It does not occur to him to question the wisdom of such a contest. As with many who grow accustomed to an easy use of power, Lear seems to believe in his own impeccable judgment — ‘it must be good for I have chosen it.’

Goneril and Regan lie obsequiously. The King grows happier. Cordelia, his “joy,” refuses to compete. She too can be stubborn and willful but also “true.” She sees her sisters display the “glib and oily art to speak and purpose not (I, i, 228-229)” and notes that its real value is to provide a cover for their “cunning”.

She offers only a daughter’s expected love, and therefore “nothing”** as far as Lear is concerned. He loses his temper, gives Cordelia away to the King of France without a dowry, and curses her — he tells her that it would have been better if she had not been born — this from a father to a loving daughter, in public.

He banishes his loyal man, Kent, because he told him that “thou dost evil (I, i, 169), and without thought divides the kingdom between Goneril and Regan, the daughters who will become nightmare creatures, the authentic “barbarous Sythian(s)” who will make friends and family “messes to gorge [their] appetites (I, i, 119-120).” In his arrogant blindness and in his desire to escape his responsibilities, Lear opens the nation to the rule of predators.

He banishes his loyal man, Kent, because he told him that “thou dost evil (I, i, 169), and without thought divides the kingdom between Goneril and Regan, the daughters who will become nightmare creatures, the authentic “barbarous Sythian(s)” who will make friends and family “messes to gorge [their] appetites (I, i, 119-120).” In his arrogant blindness and in his desire to escape his responsibilities, Lear opens the nation to the rule of predators.

Shakespeare keeps the action moving. From the large scale and public intensity and drama of scene i, scene ii opens with one man speaking directly to us, a man whom we saw wronged and humiliated, Edmund, Gloucester’s bastard son from the second family of the play, the ‘mirror family,’ whose plight further enforces Shakespeare’s portrayal of a nation suddenly beset by greed and blood betrayal.

Edmund calls “nature” his “goddess” and proclaims himself bound to her, that is, unbound to human virtues. Edmund means to violate the bonds of charity, forgiveness and kindness; he means to be deceptive, cruel and selfish. Still, he tries to charm us, to win us to his side. He tells us his secrets, his plot to destroy his brother, “legitimate” Edgar, in order that he may “prosper”. He will use his father’s shock at Lear’s disintegrating family, and Gloucester’s subsequent belief that his blood could also turn on him to portray Edgar as a conspirator who means to murder him. Edmund then uses Edgar’s trust in him to persuade him to run from his father, fearful also of his life. Diabolically, Edmund thus employs ties of love to subvert love. He takes enormous risks (all Gloucester and Edgar need is a minute or two together, and Edmund will be ruined). He acts decisively. He both horrifies us and fascinates us. He seems to acknowledge no limits on his choices.

The actions of Lear’s family continue simultaneously. Heraclitus said that “A man’s character is his fate,” and we see this theme unfolding again with Goneril (as with every other villainous character in the play who seem unable to look into themselves and doubt the moral nature of their actions). She rages against her father’s behavior in her home which “sets all at odds (I, iii, 5).” She instructs her servant, Oswald, a thoroughly sleazy piece of work, to disrespect Lear. Seeking to form a united front against the old man who gave her everything, she writes to her sister.

Kent returns in disguise; his loyalty to his master Lear is his identity. He secures his place next to Lear by beating Oswald for his disrespect.

The Fool arrives. His character’s title reflects his job, not his state of mind. The Fool is no fool. Read his lines slowly. Refer to the explanatory notes for help (always do this anyway). He is Lear’s outward conscience; a wise, physically unimposing man, older rather than younger. He has known Lear for a long time. This is a prickly, affectionate relationship, but the Fool speaks truth to power to Lear fearlessly.

Lear: Dost thou call me fool, boy? Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away; that thou wast born with (I, iv, 162-164).”

Goneril, who has schemed against her father, confronts him with complaints about his men: “So disordered … that this our court … shows … more like a tavern or a brothel ….(I, iv, 263-266).” He explodes. He calls her “degenerate bastard” and a “fiend”, and in a curse so filled with venom that it still shocks us, he calls for his daughter, flesh of his flesh, to be rendered infertile: “Into her womb convey sterility! Dry up in her the organs of increase (I, iv, 300-301).” His imagination grows more poisonous: “If she must teem, create her a child of spleen, that it may live and be a thwart disnatur’d torment to her (I, iv, 303-305).”

illustration by Andrea Armstrong

illustration by Andrea Armstrong

Hold Shakespeare’s characters responsible for their actions and words. Do not make excuses for them. Accept them in all their furies, loves, deceptions, cruelties and heroic and cowardly actions. Accept their complexity and make sense of them accordingly. You do such analyses all the time with your classmates, their parents, your teachers and coaches. You know how to think deeply about others. Apply those skills to these characters.

Lear, off to seek Regan’s comfort, his anger spent, his mood low, mutters along in response to the Fool’s attempt to cheer him. The end of Act I sees him articulate his great fear, and perhaps the most potent fear of the old everywhere: “O let me not be mad, not mad sweet heaven! Keep me in temper, I would not be mad (I, v, 50-51).” His kingdom thrown away, his peace of mind battered, refuges disappearing, he fears losing his mind, and thus himself.

* A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599 by James Shapiro

** Pay attention to the repetition of the word “nothing“. Its meanings deepen as the context of its uses expand.