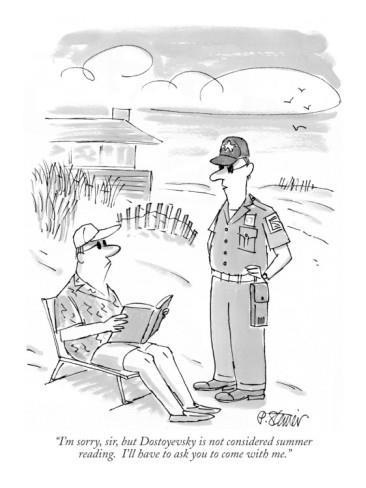

Dostoevsky is for winter reading. W.H. Auden’s wry theory of books proposed their best time to be read in the appropriate season of their mood. The Brothers Karamazov is meant for the cold. When the light goes down early, and when you awaken to frost on the inside windows, Dostoevsky’s long book provides a saving hollow where one can escape the cold in the heat and turmoil of his Russian men and women who seem forever imbued with “this thirst for life despite all (230).”

Dostoevsky is for winter reading. W.H. Auden’s wry theory of books proposed their best time to be read in the appropriate season of their mood. The Brothers Karamazov is meant for the cold. When the light goes down early, and when you awaken to frost on the inside windows, Dostoevsky’s long book provides a saving hollow where one can escape the cold in the heat and turmoil of his Russian men and women who seem forever imbued with “this thirst for life despite all (230).”

His Russians are mad for talk and more talk. For them, speaking with another meets the purest need in a human being – the need to connect, to look into a set of steady eyes and to say nothing but the truth. Dostoevsky understands that we must have these connections, that we must have someone else to whom we can unburden ourselves of our ideas and impulses, that talking with another is a revelatory experience, constantly shifting in tone and gesture and in facial expressions which we read and through which we gauge our bonds of trust and understanding. Above all, he understands that we want to be listened to by at least one other person who gives us his or her undiluted attention.

These Russians’ conversations are serious soul to soul outpourings about God, sensuality, virtue, authority, money, drink, the nature of women and men, love, religious belief, children, murder, justice, guilt, prayer, forgiveness, reconciliation, the Russian peasant, monks, an Inquisitor from fifteenth century Spain preparing to burn a returned Jesus in an auto de fe, and the Devil too, who visits Ivan in the guise of a banal, bourgeois gentleman given to statements like “I walk about here and dream (638).”

The Karamazovs begin with father Fyodor, a “bloated” man with a “fat little face”, “leering little eyes”, and a “carnivorous mouth” dotted with “stumps of black, decayed teeth (23).” Brutally selfish, a relentless seducer of women, Fyodor has been debauched by drink and greed. He is the decayed planet around which his sons revolve — Ivan, the intellectual, Alyosha, the monk and believer, and Mitya, the passionate wildman. They are wrenched to and fro by his gravitational desires.

Two other critical characters stand at opposing ends of human morality. The first, Zosima, a monk, saintly in his actions and character, withdrew from his earlier expressions of arrogance and cruelty. He developed an antenna so fine in its ability to calibrate another’s misery that “he could tell from the first glance at a visiting stranger’s face what suffering tormented his conscience (29).” He lives his new life acting in the earnest belief that “God’s truth [was] all forgiving (292).” He does not judge but serves as a kind of vessel through which Christ’s forgiveness becomes real on earth.

Two other critical characters stand at opposing ends of human morality. The first, Zosima, a monk, saintly in his actions and character, withdrew from his earlier expressions of arrogance and cruelty. He developed an antenna so fine in its ability to calibrate another’s misery that “he could tell from the first glance at a visiting stranger’s face what suffering tormented his conscience (29).” He lives his new life acting in the earnest belief that “God’s truth [was] all forgiving (292).” He does not judge but serves as a kind of vessel through which Christ’s forgiveness becomes real on earth.

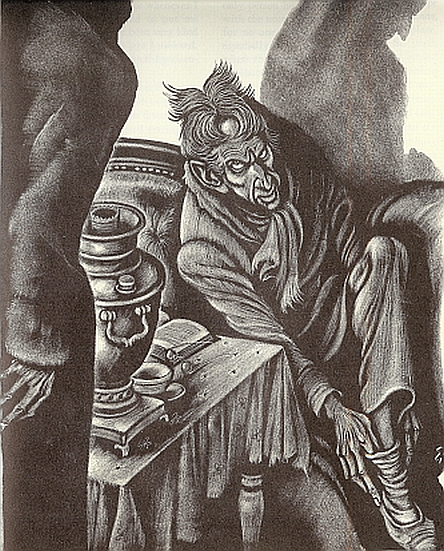

His counterpart, Smerdyakov, a servant of Fyodor Karamazov, “had an arrogant nature and seemed to despise everyone (124).” He is entirely uninterested in every other person he knows. They are not human to him. He is the flesh and blood illustration of Zosima’s definition of hell – “the suffering of being unable to love.” Consequently, he acts as if “everything is permitted (649)” him and thus he commits murder, blames it on another, and in some final shivering judgment of his own loathsome character, hangs himself.

Alyosha, the disciple of Zosima, is the center of the novel; he undertakes one compassionate journey after another “for the nature of his love was always active. He could not love passively; once he loved, he immediately also began to help (187).” Dostoevsky makes him the one character who does his best to square the austere, merciless distance of God from daily life with the heavy suffering of ordinary human beings. He visits a mad child, tries to protect another beset by bullies and rescues one from despair. He travels on errands of reconciliation between the three women who orbit the Karamazov’s. He loves his brothers.

He listens to his brother Mitya in whom passion and “sensuality [are] carried to the point of fever (79);” Mitya, who has no braking mechanism on his impulses, no capacity for reflection. In the chapter entitled “Rebellion,” he listens, terrified, to his brother Ivan muster his arguments for why God is a horror: “If everyone must suffer in order to buy eternal harmony with their suffering, pray tell me what have children got to do with it (244)?” Dostoevsky offers Alyosha as an example of what religious belief can provide as both a shield and as a refuge.

He listens to his brother Mitya in whom passion and “sensuality [are] carried to the point of fever (79);” Mitya, who has no braking mechanism on his impulses, no capacity for reflection. In the chapter entitled “Rebellion,” he listens, terrified, to his brother Ivan muster his arguments for why God is a horror: “If everyone must suffer in order to buy eternal harmony with their suffering, pray tell me what have children got to do with it (244)?” Dostoevsky offers Alyosha as an example of what religious belief can provide as both a shield and as a refuge.

The novel is filled with lines that have the speed and agility of aphorisms:

He felt “the chafings of a mind imprisoned (8).”

You are saving your souls on cabbage and you think you’re righteous (74).”

“Bring him over here, and I’ll pull his little cassock off (80).”

“Can there be beauty in Sodom (108)?”

“I loved depravity, I also loved the shame of depravity. I loved cruelty: am I not a bedbug, an evil insect (109)?”

“Wickedness is sweet: everyone denounces it, but everyone lives in it (160).”

Suddenly I fell down and got up full of ‘sirs’ (199).”

“The fanatic, emboldened by zeal, got himself going and would not be still (336).”

Smerdyakov meets with Ivan for the last time.

Smerdyakov was “not just a coward but a conjuration of all cowardice in the world taken together walking on two legs (475).”

“The presiding judge … with the hemorrhoidal face … (659).”

And my favorite because it captures so beautifully the feeling of a strange equilibrium that comes from being conscious that we are immersed in lives we know will one day end:

“It’s all so strange Karamazov, such grief, and then pancakes all of a sudden (773).”

On one level the novel presents an extended argument between a humane, Christian perspective (Dostoevsky’s sympathy) and lives lived outside that domain — debauched, impulsive, barren or driven by ideas that are literally self-destructive.

Alyosha comes to understand that “there are moments when people love crime (582).” He meets those who would be “quite ready to destroy the whole order of things (557).” He sits silently and takes in Ivan’s fury at humanity’s savagery, a moment where Dostoevsky summons a prophetic glimpse of Russia’s terrible 20th century: “There is a beast hidden in every man, a beast of rage, a beast of sensual inflammability at the cries of a tormented victim, an unrestrained beast let off the chain (241-242).” Dostoevsky sees an enduring religious faith as the only answer to suffering and to that core self-destructive nature of man.

Karamazov is a form of dramatic and intellectual fire, a rushing concentration of talk and action that tries to penetrate and understand the purest, most authentic center of the human heart. It is as ambitious an attempt to see beyond all our disguises as I’ve ever read.

Karamazov is a form of dramatic and intellectual fire, a rushing concentration of talk and action that tries to penetrate and understand the purest, most authentic center of the human heart. It is as ambitious an attempt to see beyond all our disguises as I’ve ever read.

All the quotations come from The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (the paperback cover shown at the very top of this post)

When people say ” sosh” instead of social security number” I KNOW what I have known in my heart all along. Americans think that any conversation of more than 5 seconds is not , as they say in French, inutile”.

People still hold conversations outside of America. It is part of the culture of most European countries. I suspect that in the 18th century is even normal. It was the sign of good breed to have a conversation and be able to talk about anything.. Ergo, that is why English dinners are so much fun!!