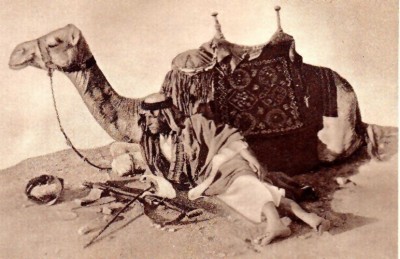

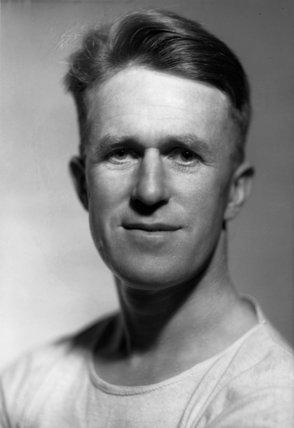

In 1918 at the end of WW I, T.E. Lawrence, 5’3” tall, weighed 80 pounds, down from his normal 112 (436). That lost 32 pounds begins to tell us something of what happened to him in the desert. For almost two years Lawrence waged guerilla warfare against the Ottoman Empire, over tens of thousands of square miles of desert, primarily with Bedouin fighters, an infidel in a land where that meant something serious.

In 1918 at the end of WW I, T.E. Lawrence, 5’3” tall, weighed 80 pounds, down from his normal 112 (436). That lost 32 pounds begins to tell us something of what happened to him in the desert. For almost two years Lawrence waged guerilla warfare against the Ottoman Empire, over tens of thousands of square miles of desert, primarily with Bedouin fighters, an infidel in a land where that meant something serious.

His gifts seem without end. He was fluent in Arabic and French, read Latin and Greek, translated The Odyssey, spent years as an archeologist, was a skilled cartographer, a machinist, a diplomat, a policy architect, a preeminent military strategist and commander, a demolitions expert, a superb shot with a pistol. He wrote a great book, one found by the bedside of many American officers today, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his story of the Arab revolt in what is now present day Arabia, Jordan, Israel, Iraq and Syria.

“He ignored wounds, boils, abrasions, infections, broken bones and pain…. He lived…beyond mere stoicism, and behaved as if he were indestructible…. (198). He schooled himself to accept pain.

He killed hundreds in battle and by dynamiting packed trains. He could not stand to be touched, probably died a virgin and yet, the evidence strongly suggests, hired a man to regularly whip him over a space of some years after the war. He was tortured and raped while held prisoner by the Turks. He executed a man, a murderer, whose life he had saved in order to prevent a blood feud between two tribes whose military assistance he was seeking. He gave away thousands and thousands of pounds sterling, was repelled by fame, sought to escape it and yet also seemed drawn to it. He was most at home in the armed forces, and he buried himself in Karachi and Waziristan to escape “Lawrence,” even changing his name. He was both monastic and had the gift of friendship. Many men and women loved him.

He told the truth about what he did in battle – this in relation to his men’s discovery of the butchering of women and children in the village of Talas by Turkish soldiers:

He told the truth about what he did in battle – this in relation to his men’s discovery of the butchering of women and children in the village of Talas by Turkish soldiers:

“There lay on us a madness, born of the horror of Talas or of its story so that we killed and killed, even blowing in the heads of the fallen and of the animals, as though their death and running blood could slake the agony in our brains (421).”

In his story “Soldier’s Home” Hemingway describes the alienation of one soldier coming home from war, the feeling of apartness that could not be bridged. After the war, Lawrence seemed forever plagued both by depression and restlessness.

Up until a few years ago, a good old man made it his habit to drive the back roads of our neighborhood, checking in, spending time. He had been a gunner on a B-17 that flew missions against Germany. He never spoke in detail about what he had seen and done.

Two former students, both marines, came back to see me a few years after graduation. Both had served in Iraq during the height of the insurgency. One had been on the wall at Abu Ghraib (not inside), and one had fought in house to house combat in Fallujah. One showed me his lab top loaded with photos that one never sees on the evening news – bodies, more bodies, bodies shattered and shredded, blown in half, eaten by dogs, half-buried in sewage and some as still and quiet as sleep. He did not boast. There was no bravado. He seemed to keep them to remind himself of the reality of his war, one already beginning to fade in contrast with job and family back in the world. He seemed to keep them to gain some sensation of the intensity that once ruled his entire life. The other marine would only say that it had been rough. He looked me in the eye. He did not appear to be haunted. He was making his own peace with the world.

Most combat veterans I have known have told few stories. I think I understand why. In contrast to them, we will forever be civilians, cut off from a visceral understanding of war. From afar, we take in reports. We watch our screens and listen to pundits and read the news. We are permanently detached. We don’t have the thousand tiny details that every other veteran carries in his bones and that do not need to be described. We don’t understand the shorthand. It must be exhausting to talk to us.

Writing a book is one thing – alone in a room, you tell yourself your stories, pushing deeper and deeper to see and remember the truth, the thing itself, so maybe Lawrence wanted to avoid telling his stories in person to others. While he was heroic in both every classical and modern sense, maybe that mantle felt false and awful. Remember, he had killed hundreds, including his own wounded men so as to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy alive.

Writing a book is one thing – alone in a room, you tell yourself your stories, pushing deeper and deeper to see and remember the truth, the thing itself, so maybe Lawrence wanted to avoid telling his stories in person to others. While he was heroic in both every classical and modern sense, maybe that mantle felt false and awful. Remember, he had killed hundreds, including his own wounded men so as to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy alive.

Maybe if you were T.E. Lawrence, there was no world to which you could ever return permanently. You became wandering Odysseus, “Aurens”, Airman Ross, Private Shaw, or as Odysseus told the Cyclops, Noman.