Last week I watched five Old Church Mennonites, men who may not drive a car, build the central frame of a post and beam barn. They spoke quietly and moved around the beams and joists with a slow, unhurried efficiency. They were working with poplar and oak that had been cut on the property. The main beams were 12” by 12” and many feet in length. The wood was green so that “it bites to the nail” as my friend described the desired effect. On three sides of the barn the sandstone walls stood thirty feet high. Northern Chester County floats on sandstone; the barn was made up of a full measure of the land that surrounded it.

Last week I watched five Old Church Mennonites, men who may not drive a car, build the central frame of a post and beam barn. They spoke quietly and moved around the beams and joists with a slow, unhurried efficiency. They were working with poplar and oak that had been cut on the property. The main beams were 12” by 12” and many feet in length. The wood was green so that “it bites to the nail” as my friend described the desired effect. On three sides of the barn the sandstone walls stood thirty feet high. Northern Chester County floats on sandstone; the barn was made up of a full measure of the land that surrounded it.

It sits on the edge of a steep, green valley; fields rise up to a wood line where tall trees were coming into leaf. The men, wearing suspenders, tool belts and straw and leather porkpie hats did much of the lifting, some smaller pieces balanced on their shoulders as they walked the beams, framed by the green of the pastures.

My friend joked with them about bring doughnuts in the morning. He knew their names, but the names of those who worked on the barn in 1897, one of several dates he found as the barn was uncovered, have been forgotten, and the names and faces of the original builders, a hundred or more years before that, are long gone. They raised the walls, kept them plumb, worked with axe and adze and planer and steadied big horses or oxen attached to pulleys to help lift the corner stones. The work mattered because it paid the bills, but also because the integrity and skill of the workers was not separate from that upon which they labored. For devout Mennonites the work is a form of worship. making the barn whole and right still matters to these men, the contemporary remnant of a long line of such builders.

Drawing quickly and confidently, my friend, a builder and a man of many talents, sketched out in my notebook the beam structure, pointing out its stress points, and then talking about the breakdown of this barn’s previous floor. Once the roof is on and doors installed, if properly maintained this structure will last for hundreds of years, or many lifetimes of men such as these Mennonites. He spoke admiringly of their work, of results made to last, built by individuals from the same small community whose photos I did not take because they might have been offended. They were making something beautiful and did so quietly, as much a part of this landscape as the grass and the sun. In watching them, I came to understand Chartres Cathedral a little better.

We did not come to Chartres auspiciously. Driving around another of France’s traffic circles, tense, trying to make the right choice on turns and arriving at the end of a 34 hour first day, from miles away we saw the Cathedral appear out of the heat mist and smog. Without notice, it was there, the spires recognizable and the whole edifice rising out of a flat landscape. Pilgrims in the 14th century would have been struck speechless. If they had approached on foot, they would have seen it bearing into view and growing larger for at least a full day. In that era of little irony and devout belief, it might have seemed to them the manifestation of the hand of God, a real, physical blessing on the land. In our globalized, secular world of industrial tourism, where crowds flock to the world’s great natural and man-made beauties, you might expect a certain dullness of eye or appreciation to set in – “oh another museum, another canyon, another church,” but no, this building retains its capacity to awe.

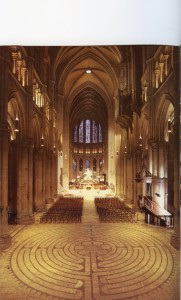

We watched batteries of rooks flocking the highest steeple. Pigeons walked its ledges. An unshaven beggar stood at the side door entrance, his eyes downcast, silent except for a whispered “Merci” when a coin dropped into the clam shell he held close to his body. Inside, the central vault opened and we stared deep into a space that extended itself vertically and horizontally. I had to stop and stare and soon found a chair and sat and remained like that for a long time, positioned out of the flow of bodies, just trying to take in the immensity of the space, the stones packed upon stone, the arches poised far above my head, the great windows high above and far away, and the altar at the farthest tip of the cross pattern that gives the cathedral its west to east axis. My eye followed the nave up and up. At 120 feet it produces a stunning sense that the architects were trying to give an idea of Heaven’s promised spaciousness within the Cathedral. There would have been nothing like this anywhere except another Cathedral and who among the poor and the farmers and tradesman in that time would have seen a second one of those?

We watched batteries of rooks flocking the highest steeple. Pigeons walked its ledges. An unshaven beggar stood at the side door entrance, his eyes downcast, silent except for a whispered “Merci” when a coin dropped into the clam shell he held close to his body. Inside, the central vault opened and we stared deep into a space that extended itself vertically and horizontally. I had to stop and stare and soon found a chair and sat and remained like that for a long time, positioned out of the flow of bodies, just trying to take in the immensity of the space, the stones packed upon stone, the arches poised far above my head, the great windows high above and far away, and the altar at the farthest tip of the cross pattern that gives the cathedral its west to east axis. My eye followed the nave up and up. At 120 feet it produces a stunning sense that the architects were trying to give an idea of Heaven’s promised spaciousness within the Cathedral. There would have been nothing like this anywhere except another Cathedral and who among the poor and the farmers and tradesman in that time would have seen a second one of those?

A dozen or so quiet walkers circled the stone –inlaid central labyrinth, symbolic of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Two women did their turn in small steps, their eyes closed, and their hands over their hearts, lips moving – winding up prayers. A few people raced around. One man in a teal colored, striped track suit, head up and eyes open, was moving so fast that he was overtaking and passing the more deliberate of the prayerful.

A dozen or so quiet walkers circled the stone –inlaid central labyrinth, symbolic of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Two women did their turn in small steps, their eyes closed, and their hands over their hearts, lips moving – winding up prayers. A few people raced around. One man in a teal colored, striped track suit, head up and eyes open, was moving so fast that he was overtaking and passing the more deliberate of the prayerful.

The southeastern front section of the Church was cordoned off; scaffolding was attached web-like to the stone walls. A workman in a white hard hat whistled softly as he filled buckets and then raised them by winch high above. Another restoration is ongoing. We could make out stained glass windows being cleaned.

Churches have occupied this hilltop since before 743 A.D. when the Vikings sacked Chartres and burned everything. Raids and warfare continued with equally disastrous results until roughly 1020, the stone and lead probably being used and reused, priests and men clearing the ruins and rebuilding. Some components of the present Cathedral date from 1134. The Church we walked into and around, in many of its elements, was constructed beginning in 1194 and consecrated in 1260; in that era those 66 years represent two full lifetimes of work.

John Ormond in his poem Cathedral Builders imagined the full life of one man, an everyman, who devoted himself to the making a cathedral. Each day they “climbed on sketchy ladders towards God” and each night “lay with their smelly wives/quarreled and cuffed the children, lied/Spat, sang, were happy or unhappy.” They “saw naves sprout arches, clerestories soar.” When he “grew grayer, shakier” and “got rheumatism,” he left “the spire to others” and at completion “stood in the crowd/Well back from the vestments at the consecration” and from that vantage point, his name never mentioned, lucky to be alive at that moment of fruition, one of the anonymous thousands who had labored over hundreds of years, he “Cocked up a squint eye and said,’ I bloody did that.’”

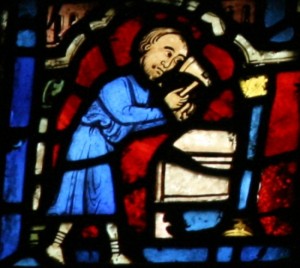

Malcolm Miller, in his book Chartres Cathedral, writes that “The Merchant Brotherhoods donated forty three windows for the new cathedral, and their ‘signatures,’ in more than one hundred scenes, have caught them timelessly in their occupations…. (12)”

Malcolm Miller, in his book Chartres Cathedral, writes that “The Merchant Brotherhoods donated forty three windows for the new cathedral, and their ‘signatures,’ in more than one hundred scenes, have caught them timelessly in their occupations…. (12)”

Here, from the Noah Window, a carpenter weilds a tool on a chest. In others, fishmongers, vintners, wheelwrights, shoemakers, water carriers, bakers, and stone masons all apply their trades. “No names have survived (13).” We see their labor. We can intuit some rudiments of their skills, but the work is a collective, communal effort and symbolic of their calling, symbolic of their offering. The work matters, the names do not. Ormond’s poem gives imagined life and voice to one person, but even in this poem, the speaker goes unnamed. Who will remember the name of the man operating the winch in 2012 or the woman I could see on the far side of the scaffolding, kneeling and delicately scraping the grime on a window? The product of their work will remain, its skillful application representative of their own integrity and dedication.

Here, from the Noah Window, a carpenter weilds a tool on a chest. In others, fishmongers, vintners, wheelwrights, shoemakers, water carriers, bakers, and stone masons all apply their trades. “No names have survived (13).” We see their labor. We can intuit some rudiments of their skills, but the work is a collective, communal effort and symbolic of their calling, symbolic of their offering. The work matters, the names do not. Ormond’s poem gives imagined life and voice to one person, but even in this poem, the speaker goes unnamed. Who will remember the name of the man operating the winch in 2012 or the woman I could see on the far side of the scaffolding, kneeling and delicately scraping the grime on a window? The product of their work will remain, its skillful application representative of their own integrity and dedication.

The voices of singers or a Gregorian Chant must fill this space with something physical in its palpability. We heard a choir of all women sing at Mont Saint Michel on Palm Sunday. The heavy scent of incense rose in front of the altar and drifted to us. Ritual adds to the sense of harmony. Chartres and Notre Dame and Mont Saint Michel and other like places of worship, built and rebuilt over centuries, seem like an initial effort to create a perfect harmony in what was then a difficult, often murderous, disease ridden, brutal world. Life in all its messiness would have come into this Cathedral. Markets filled its courtyards. Houses once pressed up against it. Animals would have wandered inside. The lame and blind, beggars and those whose skin was eaten by pox would have sought healing and sanctuary. They too would have walked the Labyrinth, set in the floor to match the placement of the sublime Rose Window; an invisible line connects the center of the Rose to the center of the Labyrinth – Heaven lies on the same line as Jerusalem.

Most contemporary church design seems either over the top and vulgar or so utilitarian as to be soulless. Many look like convention halls and are invariably dark, the better to see the videos and images flashing on the huge screen over the preacher’s stage. I have warm memories of the light filled little chapel on Inishmore in the Aran Islands where my friend and I heard a Mass in Gaelic, and rich childhood images of St. Mary’s in Lebanon, a big Irish immigrant Church built in the 1880’s. I think that a Church has to have a spirit, a grounding in another unseen reality, one that begins in our imaginations and then connects to our feelings of awe and wonder and that encourages us to settle into something calm and abiding. We need to be able to breathe deeply in them. Spaciousness and light and song help all that be accomplished. The spaces of Chartres made by all those workers over all those years helps, even today in our ugly, profane age, to create a feeling of ascension, of a better world, a sacred world beyond this one.

Most contemporary church design seems either over the top and vulgar or so utilitarian as to be soulless. Many look like convention halls and are invariably dark, the better to see the videos and images flashing on the huge screen over the preacher’s stage. I have warm memories of the light filled little chapel on Inishmore in the Aran Islands where my friend and I heard a Mass in Gaelic, and rich childhood images of St. Mary’s in Lebanon, a big Irish immigrant Church built in the 1880’s. I think that a Church has to have a spirit, a grounding in another unseen reality, one that begins in our imaginations and then connects to our feelings of awe and wonder and that encourages us to settle into something calm and abiding. We need to be able to breathe deeply in them. Spaciousness and light and song help all that be accomplished. The spaces of Chartres made by all those workers over all those years helps, even today in our ugly, profane age, to create a feeling of ascension, of a better world, a sacred world beyond this one.

We circled the Cathedral outside, and behind it stopped at an overlook. An old man read on a bench, couples wandered by, arm in arm, and this young man sat on the wall beside his wonderful bicycle, looking down at the town and the labyrinth cut into a small park and at this hour filled with laughing high school kids. All around the Cathedral trees and flowers were coming into bud. Inevitably, my eyes came back to the Church and its massive buttresses, its sculptures of saints and gargoyles and many small unobtrusive doors, the details that roughed the smooth surfaces of this particular monument to absolute faith.

Completing the circuit, I again entered the nave and was struck by a tiny older Japanese woman, alone, in a dark raincoat and dark hat, who stood just outside the labyrinth and its circling crowd. Her hands were folded against her chest. Her head was raised, but her eye were open; she slowly, very slowly with many stops, turned within the area of one stone of the floor, her eyes sweeping the nave and the arches of the roof, the windows and the light.

Later I waited behind her at our hotel directly across the square from the Royal Portal and the North and South Towers. In a combination of French and English she thanked the owner and said that she would be back the following year when she hoped all the restoration on the South Choir would be finished. She never stopped smiling. She said that Chartres was the best town and the Church the best place, a place of peace she called it. She would come back, she said, again and again.