A friend has died. This is what we saw, now, and long ago.

In an airy, light-filled space, the main sanctuary of a synagogue near a large Midwestern city, his three children told stories about D as he had been as a father. When his oldest daughter did her residency in the busiest emergency room in the city, he came, sat amidst the chaos of all that speed and blood and pain. He watched over her and gave her the quiet strength of his presence. His son remembered that, as a child, the finest part of his day had been hearing the garage door open at 6:30 and knowing that his best playmate had arrived home. His younger daughter told of her delight in watching this big man with this big brain hold his dogs in his arms and speak baby talk gibberish to them until everyone around him howled with laughter. Lawyers from his firm spoke of his unsurpassed skills as a negotiator and advisor, of his sublime ability to both explain complex areas of the law and persuade adversaries to accede to his client’s best interests. They told of his willingness to teach and listen. One described the reactions of his colleagues upon learning of his sudden death, of grown men weeping over the phone, of one who cried out, “No No No No.”

This well known UK aphorism matches D’s most apparent quality

This well known UK aphorism matches D’s most apparent quality

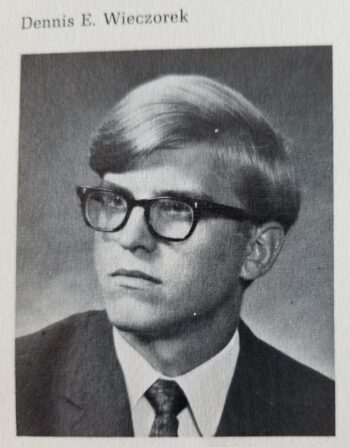

My friend and I listened to their descriptions of a man whose fundamentals of character we had seen as a 15 year old, in a ninth grader, and now those 62 year old fully realized qualities registered as completely familiar. He was the least adolescent of all our group of 8 or 10, the most even tempered, the least sharp tongued, the least cruel. He was effortlessly smart. He just knew things, as if his mind operated within another realm of physics. A fervor attaches to the intelligence of some really bright people; they give off heat. You can sense how their minds work. It is possible to gather insights about their mechanics. Not D.

His intelligence had the attribute of opacity. It_was_fully_present, always.

Inseparable. Seamless. Immediate.

When he was being serious, he could offer an answer in class, an opinion about politics or books, a reference to a connecting piece of knowledge — all of these cogent and insightful – and I would wonder from where it had come. It snapped in the air as if it possessed a physical force.

I do not remember that he ever made a display of arrogance regarding this gift. For example, he voiced genuine surprise at the weight of both his SAT and LSAT scores and said that when law school presented itself as a real possibility, he was both gratified at having discovered a direction for his life and startled by his success.

Lots of sharp people have separation points in their gift – “Yes, he or she is wonderfully bright, but, you know, what a jerk,” or “How arrogant!” or “My God, such a creep around women,” or “Yes, with the exception of that narrow range.” With D, no clause followed any evaluation of his intelligence; this sense of wholeness, I think, went to his core.

If we know someone long enough, over decades, we are able to see the curve of his or her life and thus gauge the stations of time where cause and effect seems to break down – where character shifts radically without any reason apparent to the less intimate observer. D’s character, by all appearances, based on the specifics of the stories told at his Service, never changed. Its fundamentals remained, bedrock that had been exposed for all to see for as long as we had known him.

I had lost touch with D for decades, but the stories we heard from his children and friends and wife seemed to be the consequence of his personal evolution over time. They were indicative of the ways in which a good marriage, fatherhood, and the mastery of a discipline will broaden and deepen a man. This fact however is critical – both my friend and I recognized the man who had been the boy.

In the summer of 1972 the Rolling Stones released Exile on Main Street and began touring. Our group waited outside a store all night and then ran through aisles and up escalators, yelping barbarically, to get to the Ticketron Office first.

The Stones at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, 1972

The Stones at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, 1972

The Stones were terrific, and I remember D standing on a chair, long hair winging back and forth across his face, dancing wildly. He was always great fun.

I can bring him back and see him driving his father’s car, a big gold Torino that steered like a 2000 pound wagon. He had to use both hands to make turns. I can see him using that big lineman’s body under the boards, blocking out and then making the outlet pass. I can still see him smoking Salems and playing Risk late into the night and then driving home at dawn while the milk trucks were making their rounds. I can see him on the Ham Production Line at Berks Packing, trimming ham blocks and wrapping them in filmy cellophane, and helping push his father’s car out of the parking lot at Eastern Machines with Hurricane Agnes flood waters already at the levels of the doors. I can see him at the ruined concert and anti-war rally at the Reading Band Shell, running, with the rest of us, from tear gas and police in gas masks and carrying truncheons. And at an Albright College Vietnam Teach-In, listening, his expression fixed and intense. And at a bar, laughing. And laughing at 17, 18, 19, a young man who never put on airs or boasted.

For all our feelings of rebelliousness, for all our multiple transgressions, only one or two were shameful and dire. We were mindful of pleasing our fathers and not disappointing our mothers. We were all struggling toward some workable version of manhood. I think D got there before some of us, and then he just kept getting better at it.

For all our feelings of rebelliousness, for all our multiple transgressions, only one or two were shameful and dire. We were mindful of pleasing our fathers and not disappointing our mothers. We were all struggling toward some workable version of manhood. I think D got there before some of us, and then he just kept getting better at it.

A coherent vision of D’s life unfolded at his memorial: a good man at the very center of a complex, overlapping web of family, friendships and work relationships. To be suddenly plucked from the web without warning is cruel and unjust and so random as to make one furious. We all must leave, but to leave with so much to do …. D had so much yet to give and to receive.

And yet, both of us left the Service heartened at the superb life D had made, at how his decency and brilliance had made the lives of hundreds upon hundreds so much better. Yes, as the rabbi said in her moving elegy, “the light has been diminished by his passing,” but O how it burned while he lived. We should all be so remembered. We should all live lit from within by such fire.

A beautiful, moving memorial. Z”L

It makes me wish I had met him. I’m sorry.

Fantastic