Almost every day I come across a sentence, an image, a line of poetry, or a sharp piece of dialogue, and I try to remember it. The inclination to think in terms of how I might use it in a classroom lesson has never left me. I turn down pages, underline, write in margins, tear newspapers to pieces and stack fragments on my desk for later use. Sometimes I add bits to the interior of my money clipped cards where they rest between my book list and the photo of Joe Namath throwing a jump pass against the Oakland Raiders. Sometimes whole books move me so that I must write about them so as to learn what I think. Sometimes I want to report on whole sections of a book because they have forged such a strong memory in me. Such is the case with Ian Frazier’s conclusion to his chapter on Crazy Horse.

What so appealed to me right now in Frazier’s praise was this: he describes a man who lived independently of the smothering effects of yearning to belong. Crazy Horse sustained himself within his natural and tribal world as completely as if both were genetically intertwined; he did not need nor desire, that critical word, the white’s promises or their praise. He refused to become an object. Defeated, he would not say “Yes.” Captured, he would not say “Please.” He remained resolutely himself, a person of integrity even in his agony and death.

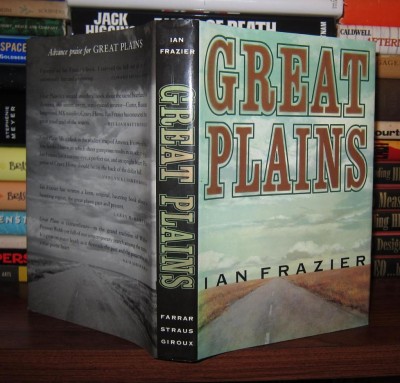

Please read this short biography of Crazy Horse before you read the selection from Ian Frazier. I also encourage you to read Larry McMurtry’s book Crazy Horse: A Life and all of Frazier’s Great Plains, a book of a generous spirit and beautiful.

Crazy Horse Memorial, Thunder Mountain, the Black Hills of South Dakota, near Custer, 2014

“Personally, I love Crazy Horse because even the most basic outline of his life shows how great he was; because he remained himself from the moment of his birth to the moment he died; because he knew exactly where he wanted to live, and never left; because he may have surrendered, but he was never defeated in battle; because, although he was killed, even the army admitted that he was never captured; because he was so free that he didn’t know what a jail looked like; because at the most desperate moment of his life he only cut Little Big Man on the hand; because unlike many people all over the world, when he met white men he was not diminished by the encounter; because his dislike of the oncoming civilization was prophetic; because the idea of becoming a farmer apparently never crossed his mind; because he didn’t end up in the Dry Tortugas; because he never met the President; because he never rode on a train, slept in a boardinghouse, ate at a table; because he never wore a medal or a top hat or any other thing that white men gave him; because he made sure his wife was safe before going to where he expected to die; because although Indian agents, among themselves, sometimes referred to Red Cloud as “Red” and Spotted tail as “Spot,” they never used a diminutive for him; because, deprived of freedom, power, occupation, culture, trapped in a situation where bravery was invisible, he was still brave; because he fought in self-defense, and took no one with him when he died; because, like the rings of Saturn, the carbon atom, and the underwater reef, he belonged to a category of phenomena which our technology had not then advanced far enough to photograph; because no photograph or painting or even sketch of him exists; because he is not the Indian on the nickel, the tobacco pouch, or the apple crate. Crazy Horse was a slim man of medium height with brown hair hanging below his waist and a scar above his lip. Now, in the mind of each person who imagines him, he looks different.

I believe that when Crazy Horse was killed, something more than a man’s life was snuffed out. Once, America’s size in the imagination was limitless. After Europeans settled and changed it, working from the coasts inland, its size in the imagination shrank. Like the center of a dying fire, the Great Plains held that original vision longest. Just as people finally came to the Great Plains and changed them, so they came to where Crazy Horse lived and killed him. Crazy Horse had the misfortune to live in a place which existed both in reality and in the dreams of people far away; he managed to leave both the real and the imaginary place unbetrayed. What I return to most often when I think of Crazy Horse is the fact that in the adjutant’s office he refused to lie on the cot. Mortally wounded, frothing at the mouth, grinding his teeth in pain, he chose the floor instead. What a distance is between that cot and floor! On the cot, he would have been, in some sense, “ours”: an object of pity, an accident victim, “the noble red man, the last of his race, etc. etc.” But on the floor Crazy Horse was Crazy Horse still. On the floor, he remembered Agent Lee, summoned him, forgave him. On the floor, unable to rise, he was guarded by soldiers even then. On the floor, he said goodbye to his father and Touch the Clouds, the last of the thousands that once followed him. And on the floor, still as far from white men as the limitless continent they once dreamed of, he died. Touch the Clouds pulled the blanket over his face: “That is the lodge of Crazy Horse.” Lying where he chose, Crazy Horse showed the rest of us where we are standing. With his body, he demonstrated that the floor of an Army office was part of the land, and that the land was still his.”

I believe that when Crazy Horse was killed, something more than a man’s life was snuffed out. Once, America’s size in the imagination was limitless. After Europeans settled and changed it, working from the coasts inland, its size in the imagination shrank. Like the center of a dying fire, the Great Plains held that original vision longest. Just as people finally came to the Great Plains and changed them, so they came to where Crazy Horse lived and killed him. Crazy Horse had the misfortune to live in a place which existed both in reality and in the dreams of people far away; he managed to leave both the real and the imaginary place unbetrayed. What I return to most often when I think of Crazy Horse is the fact that in the adjutant’s office he refused to lie on the cot. Mortally wounded, frothing at the mouth, grinding his teeth in pain, he chose the floor instead. What a distance is between that cot and floor! On the cot, he would have been, in some sense, “ours”: an object of pity, an accident victim, “the noble red man, the last of his race, etc. etc.” But on the floor Crazy Horse was Crazy Horse still. On the floor, he remembered Agent Lee, summoned him, forgave him. On the floor, unable to rise, he was guarded by soldiers even then. On the floor, he said goodbye to his father and Touch the Clouds, the last of the thousands that once followed him. And on the floor, still as far from white men as the limitless continent they once dreamed of, he died. Touch the Clouds pulled the blanket over his face: “That is the lodge of Crazy Horse.” Lying where he chose, Crazy Horse showed the rest of us where we are standing. With his body, he demonstrated that the floor of an Army office was part of the land, and that the land was still his.”

Ian Frazier, pages 117-119

Thanks Mike.. the essence of real character. It was beautiful written to describe this man. Men and women like this are not diminished by death.

Mike — I really enjoy this piece — it also speaks of you as I remember you. Thanks.

Terry