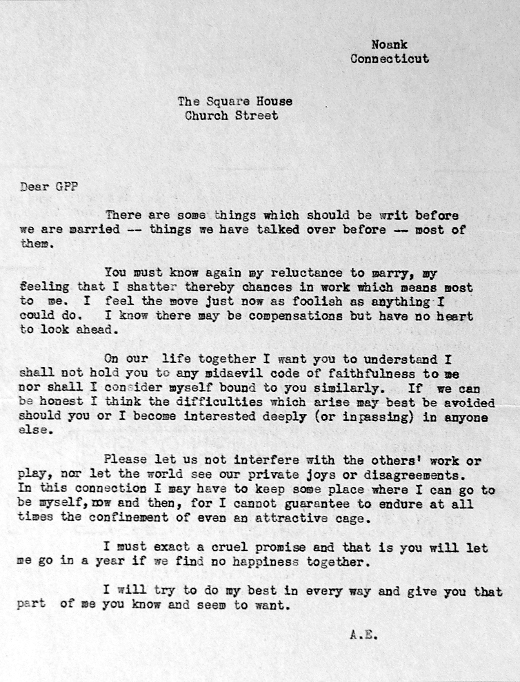

In paragraphs built around a subtext of flight, Amelia Earhart tries to spin and roll away from her impending marriage. Her fiancee, George Putnam, had asked her to marry him six times; she finally said yes, but then in early 1931, shortly before the ceremony, she wrote a letter of six paragraphs. Read it aloud. It feels like listening to something big and desperate batter itself against thick walls. She writes this letter to a man she loves, but her sense of autonomy is as durable and abiding as her skin. To give it up would be to accept being flayed. Look at her key word choices: reluctance, shatter, foolish, bound, difficulties, confinement, cage. Only in her final sentence does she make a halting promise: “I will try to do my best in every way [to] give you that part of me you know and seem to want.” The brittle looking original of the letter, displayed in a small frame in The National Portrait Gallery, looks as if it is contracting inside the glass.

In paragraphs built around a subtext of flight, Amelia Earhart tries to spin and roll away from her impending marriage. Her fiancee, George Putnam, had asked her to marry him six times; she finally said yes, but then in early 1931, shortly before the ceremony, she wrote a letter of six paragraphs. Read it aloud. It feels like listening to something big and desperate batter itself against thick walls. She writes this letter to a man she loves, but her sense of autonomy is as durable and abiding as her skin. To give it up would be to accept being flayed. Look at her key word choices: reluctance, shatter, foolish, bound, difficulties, confinement, cage. Only in her final sentence does she make a halting promise: “I will try to do my best in every way [to] give you that part of me you know and seem to want.” The brittle looking original of the letter, displayed in a small frame in The National Portrait Gallery, looks as if it is contracting inside the glass.

She started late. She was 23 when she had her first ride in bi-plane. Her first flying lesson came six days later. Six months later, in July of 1921, she had bought a bright yellow two seater that looked like an elongated box attached to cardboard wheels. She took it up to 14,000 feet and set a record. Five years after Lindbergh she flew alone across the Atlantic. She flew alone from Honolulu to Oakland, from Mexico City to Newark. In 1937 she and a navigator disappeared over the Pacific on one of the final legs of an around the world trip.*

Her Lockheed Vega resting in the center of a room devoted to her at the Smithsonian is handsome — it looks like an art deco creation instead of a practical machine. She once wrote, “After midnight the moon set and I was alone with the stars. I have often said that the lure of flying is the lure of beauty, and I need no other flight to convince me that the reason flyers fly, whether they know it or not, is the aesthetic appeal of flying.”*

That is how I imagine her — alone, focused, completely aware down to every last nerve ending, thousands of feet above the earth, watching the cartographic loveliness of river lines and dirt roads and fields; watching hawks glide below the plane; disappearing into clouds and climbing above them to a sky devoid of any other human creation. Maybe being alone with so much beauty for so many hours makes someone braver. If so, what torrents of happiness she earned!

That is how I imagine her — alone, focused, completely aware down to every last nerve ending, thousands of feet above the earth, watching the cartographic loveliness of river lines and dirt roads and fields; watching hawks glide below the plane; disappearing into clouds and climbing above them to a sky devoid of any other human creation. Maybe being alone with so much beauty for so many hours makes someone braver. If so, what torrents of happiness she earned!

Yes, you have nearly captured her !

Single-mindedness of purpose, we generally call it, she was just about nearly oblivious to anything else going on around her, including George.

Fame and Fortune was her endeavour and through her impetuousness, it killed her.

David Billings.